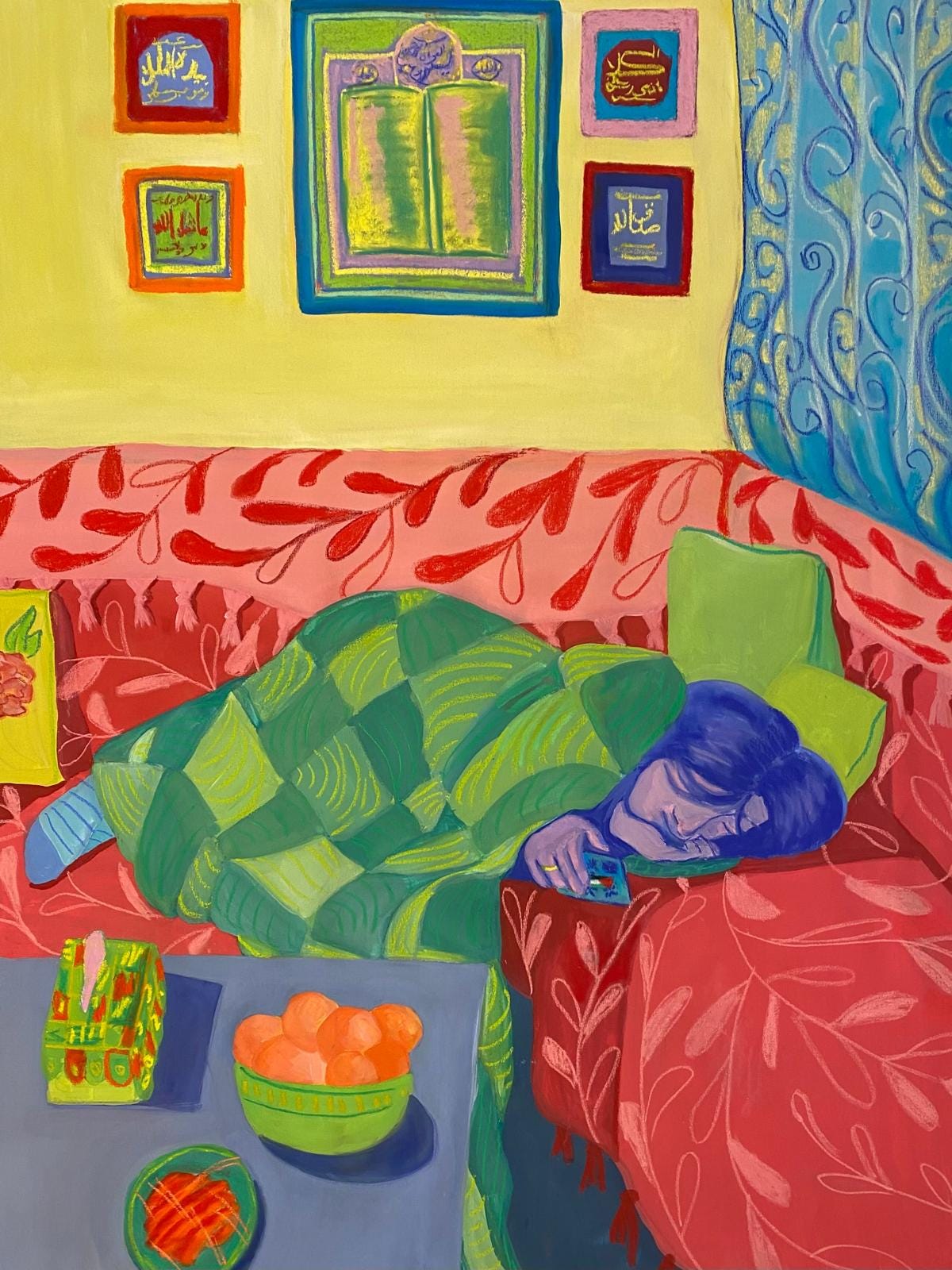

Soft and bright colors are a reminder that home is malleable matter. Manipulating colors transforms an already vivid present into an imagination, of something much brighter than itself. To be home is to be embraced. To be home is to be surrounded by the relics of memory. To be home is to be haunted, by what is, and what once was.

Ameni Abida’s Waiting for Maghrib (2024)

110 x 145 cm

Soft pastels and acrylic on canvas

Exhibited at @wusumgallery ‘s A Home Without Dates Will Starve

Soft and bright colors are a reminder that home is malleable matter. Manipulating colors transforms an already vivid present into an imagination, of something much brighter than itself. To be home is to be embraced. To be home is to be surrounded by the relics of memory. To be home is to be haunted, by what is, and what once was.

I took this photograph, knowing that my sister, Ameni Abida, would eventually paint it. She is pictured resting on the couch of our grandparent's house in Nabeul, Tunisia, under the cozy ethnic wool blankets. It is a corner of a couch that she and I compete over daily. The culmination of our shared tenure on our grandparent’s living room couch is Waiting for Maghreb (2024), currently at Wusum Gallery’s exhibition “A Home Without Dates”. In this scene, sound is absent, but I will reveal to you what you cannot hear. The loud blasting of the television news is absent, that and the loud ticking of the living room couch. Together, they are a tormenting symphony. Blue wrought iron decorates the right side of the painting, with strokes of pastel lines on top of the paint. Reality seems so delightful, enough that I would want to take a bite off the wrought iron, or the couch. It is all sweet in Ameni’s world, but nostalgia is a dish best served lukewarm.

Our late grandfather was obsessed with the news. It was all that we heard as soon as we crossed the gates of their house. But the sound of the news still haunts the corridor of my grandparent’s home, and every word uttered by news anchors is a reminder of our grandfather’s trace in between the walls. The bowl of oranges reminds us of the connection to the homeland, a reference to the orange trees in my grandparents’ garden, some of which had died in the year following my grandfather’s passing. Above the couch are different Quranic verses, reminding us of God’s presence in the house. Displaying Quranic verses is both to bless the house, as well as to protect its inhabitants from evil, be it Jinn, or the evil eye of others.

If you look closely at the main figure’s face, the facial expression and body language are in sheer contradiction to the wonder and whimsy all around her. Frowning, squeamish, curled up and uncomfortable, holding her phone between her fingers. That is the contradiction of what it means to be safe. The bold colors reimagine a world that is outside of what we know now, and what we have seen now, a world that lacks color. Whilst we witnessed the ruthless killing of Palestinians, many of us are in exile on a living room couch.

Waiting for the Maghrib refers to the fast that Muslims undertake every year during Ramadan, from sunrise to sunset. The fast closes with the Maghrib prayer, once the sun sets, conviviality, warmth, and delicious food populate tables worldwide. The half-hour before sunset is the most difficult time of the fast, the stomach rumbles, the temper shortens and the mouth dries from the lack of water. One lays down and rests until it is time to eat. But in Gaza, fasts were not broken after the Maghrib and were prolonged due to the deliberate starvation of Palestinians. We can ask ourselves from that, a simple question - how does one stand up to the art of witnessing? Since October 7, 2023, we have witnessed a genocide unfold before our eyes, and are paralyzed on the living room couch.

The appropriate Gen Z language to describe this scene would be “doom-scrolling” and “girl rotting”. The former refers to the excessive consumption of the news, whilst the latter is the activity of laying down “rotting” without any activity. But I would add another reference to Gen Z language is “delulu”, which is shorthand for the word delusional, and refers to anyone who has overly idealistic fantasies and imaginaries. Abida’s use of colors could easily fall under the delulu category if it weren’t for the sheer discomfort of her face. And yet, “delulu” entering internet lingo shows encompasses the Gen Z experience, it is not just the “girlies” who are delusional, but everyone. Many dreams are reduced to ashes before a kid can even grow up. We failed the kids, not just in Palestine, but everywhere. Even for those of us who do dream, we live in delusion. We think we have a future in a collapsing world. I do not want to be a pessimist, so I leave you with James Baldwin’s words “I have never been in despair about the world. I am enraged by it. I can’t afford despair. You can’t tell the children there is no hope”.

For many of us, this is a familiar sight, raising questions on how we cope with witnessing an unrecognizable world across our screens. We realize how fortunate we are to call places home, places that we can return to, places who’s walls still withstand and are not continuously bombed. Who do we want to be when death unfolds whilst safe under the covers? We cannot escape the confines of violence, the shared frustration and pain, and the quest for justice. We witness the unthinkable every day, and it feels apocalyptical. I try not to, but sometimes I am paralyzed and I wonder if I am not spending hours on the same living room couch waiting for the world to end.

You can check out Ameni’s works here. This piece is an experimentation with art writing.