[Preface : This piece was written between July and August 2021, revisited sometime in January 2023, and again in October 2023. I share this as a commemoration of the beautiful life Baba Latif lived. Allah Yeharmo. ]

His name is Abdelatif and I think there’s no other name that would suit him better. Servant of the all-gentle and kind. The clock reads half past two. By now, my grandfather is awake from his second nap of the day and had his daily walk. His bedroom is almost pitch black, except for the little light that comes through the gaps of the closed window blinds. He lies on his right side half covered by the blue flower patterned bedsheets my aunt brought two summers ago from Ivory Coast. He listens intently to the radio with his earphones on, staring into the floor. As usual, I interrupt, sitting right next to him.

‘اهلا بابا، شحالك؟’1

‘Hello Baba Latif, how are you today?’

He reaches for my hand and kisses it. Carefully unplugs his radio and takes his earphones off. I used to wipe off the sloppy kisses my grandfather greeted me with once he turned away, and I occasionally caught my mom’s stare of disapproval. How could I, a nine year old girl, wipe off the wet kisses of my loving grandfather? I lacked indiscretion, social tact. I wonder if he ever noticed, or just chose to ignore it. My grandfather no longer gives me the sloppy kisses he used to.

‘ياسمين يا بنتي، نحي الكمامة بش نشوف وجهك’

‘Yesmine, my daughter, could you take off your face mask so I could see your face?’

‘ بابا انا نخاف عليك…نحلك الشباك؟’

‘Baba, I worry for you.’ I quickly change the topic. ‘Should I open the window?’

‘عيش بنتي زيد غطيني’

‘My dear daughter, could you please cover me with the blanket?’

I know the last few days were difficult. He is not getting much sleep, and refuses to use the air conditioning during this unforgiving August heatwave. Our city is known for its healing breeze and fresh air, but lately heaven’s doors seem to have shut down, leaving us nothing but heavy air and occasional power outages. But today, he is in a much more talkative mood.

‘شفت يا بابا، الطقس تحسن البارح في الليل ، حليت الشباك في الفجر و حسيت بنعومة الخريف’

‘Did you notice Baba, the weather improved last night? I slept with the windows open and felt autumn’s softness at dawn.’

He looks at me, in slight confusion.

‘ياسمين، شنو رئيك بلي صاير في تونس ؟’

‘Yesmine, what do you think about what is happening in Tunisia?’

I pause. It is a loaded question. Healthcare is on the brink of collapse, and the country is experiencing the worst covid crisis in all of the African continent. I feel like Tunisian partisanship keeps getting more polarized by the day. Our parliament has been frozen for an indefinite amount of time. I live in nuances, and the only consensus from the three different echo chambers on my twitter timeline is things are heading for the worse. 2

‘Baba, is it okay if we don’t talk about the news today?’

He smiles and shrugs his shoulders.

‘We can talk about history if you would like.’

‘بابا تتذكر الاستعمار الفرنساوي في تونس؟’

‘Baba, do you remember French colonialism in Tunisia?’

اى بينسور كان عمري تقريباً ١٣ سنة و قبل الاستقلال مكانش عدنا شرطة. كان فما الجندارم كانو في كل بلاصة في صفاقس و قتلوا ناس انذكر قبل ١٩٥٦ البلدان للي كانوا اسميهم فرنسية تبدلوا بإسم عربي

‘Of course I was about thirteen years old and before independence we did not have police, we had the gendarme. They were everywhere in Sfax and killed people. I remember after 1956 the cities that had French names were renamed to be given Arabic names.’

The foggy childhood memories I could recollect of my grandfather are in two distinct categories. Either he was in the living room, in front of the television listening to the news, with the volume high enough for the neighbors to hear the broadcast. Or else in the garden, tending to his sixty something birds, cutting up leftover bread and showing us (his grandkids) how to fill their water tanks. I saw him as an elusive figure that was in constant flux between the backyard and the living room. He sat so close to the television, so close that he could soon join the newsroom and give a full rundown of a week's worth of football match updates. Every night for dinner he has the news accompanied by a side of soup. He only ever watches the news in total darkness. I could not understand how he stomachs the news, but I quickly understood that I have more in common with him then I think. A curiosity for the world perhaps.

Not much has changed since then, although illness and old age made him more of a homebody.

My uncle enters my grandfather’s bedroom to administer his insulin shot, followed by Mama Rachida, who brings him lunch to bed. Couscous, grilled fish, some olives, a cup of water and a transparent box of medicine on a silver platter.

يا رشيدة وين صحنك؟ إجاء اكل بحذايا .

‘Rachida, where is your plate? Come eat with me.’

He can’t sit on chairs anymore because of his surgery. He spends his whole day lying in bed, and we try our best to bring our different worlds to him. On his bedside are the figs my aunt brought him from a tree that grows near her house in Tunis.

بش نزرع الكرموس في الجردة كي صحتي تتحسن [...] كل ما ربحت في حياتي هما زغاري

‘I am going to plant these figs in the garden when my health improves [...] all that I have gained in my life are my kids.’

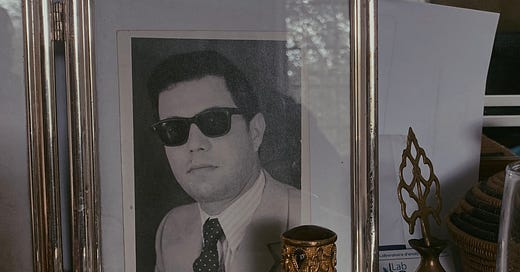

Baba Abdelatif enjoys coffee in the afternoon. By then, the entire family, my grandma, my mother, my uncle, my aunts, my cousins and I are in the bedroom. The blinds are now open, revealing the wilted sunflowers planted outside the window, and the neighbour’s ferocious dog barking at a cat strolling near him. Three generations in a now well lit room, with a symphony of smells between the Turkish coffee and the Jasmines my grandfather picked on his daily walk, left on the vanity, next to my grandparent’s newly wed photos from 1960.

I leave my grandparents bedroom and sit on the veranda’s steps. Summers have come and gone where we would usually all sit here, surrounded by colorful tiles, unable to escape mosquito stings. Sometimes, I think of this house as something close to a miracle. A house built in 1977, a decade after Baba Latif and Mama Rachida moved to Nabeul from Sfax, has become the centerpiece of not only mine, but everyone else’s lives. A house built in a city where my grandfather was deployed as a nurse to help with the tuberculosis vaccination campaign in the 1960s. He loved Nabeul enough that he decided that was where we would be, and there was no better place he could have picked.

I don’t think my grandparents realize how special this place is.

The white wrought iron gate shrieks, and my father enters the main gate of the house, with a cake in his hand. It reads

مبروك النجاح لأحفاد بابا عبداللطيف وأمي رشيدة

“congratulations to the success of the grandchildren of Baba Abdelatif and Mama Rachida”

Baba Abdelatif grew up in the era of Tunisian history where the country’s first president, Habib Bourguiba made education mandatory and free for all. Education is so important to him, in a way that I do not think I will understand. I think it is a mix of being a greater symbol of post-independence decolonization, and gives him a sense of optimism that his descendants will live a better life than he did. Because of that, nothing could make him happier than knowing that his grandchildren were doing well in their studies. So we go one by one, celebrating each of his twelve grandchildren, with rounds of applauses marking each one. Two masters graduates, one medical student, one final year undergraduate student, three in highschool, three in middle school and two in kindergarten. This afternoon, Latif does not taste the caramel chunks between layers of chocolate cake, whipped cream and ground nuts, but the sweet collective victories before him. I don’t think I have ever seen his smile extend this widely.

I stand to stretch my legs numb from sitting on the carpet. I look around the room and try to navigate the maze, that is of my cousins sitting on the floor. I notice the photographs under the glass of my grandparent’s dressing table, that tell me family stories of a place I still do not fully understand or know. It quickly fills my body with an overwhelming sense of anxiety on the prospect of my departure.

I am in the stage of the summer where I take mental photographs of my surroundings, try as best as I can to remember every single detail I possibly can. I love this country, I love this place, but it barely feels like my absence when I leave. It moves on without me, and to my disappointment, my return usually involves a new deficit, a decay, an absence. My aunt stands up and collects the plates of half eaten cake slices, my mother follows to collect cups of coffee. Everyone gradually leaves the room until it is just me and Baba Abdelatif again.

‘So, when are you leaving?’ he asks

‘I’m going back to Abu Dhabi tomorrow. We are heading to the airport at 10am. I can’t believe summer break is coming to an end. Does time go by quickly for you?’

‘Yes sort of, but that’s because I spend the entire day asleep in my bedroom’

I stop fidgeting with the knobs of his radio.

‘Would you like to study in Tunisia’ he asks

‘If I could, I would have stayed here Baba. I want to do research about the history of Nabeul, but I just can’t’

‘May God help you succeed, and may you get your PhD’

‘Ameen, thank you’

‘Do you think I’ll be around for your PhD?’

‘Of course, inshallah. And I’ll translate it from English so you could read it.’

‘I doubt it, but your next research should be on the history of the Amazigh in Tunisia, because we don’t talk about it here enough.’

‘That sounds like a great idea.’

My voice cracks slightly. He stands up and walks me and my mother to the door. We are going home, and he usually locks the house door at night. He stands at the edge of the wrought iron gate, watching us drive away, I lower my window.

تصبح على خير يا بابا نشوفك على خير ان شاء الله

‘Goodnight Baba Latif, I’ll see you soon inshallah in good condition’

We drive away and he gets smaller and smaller from the distance.

That was the last time I ever saw or spoke Baba Abdelatif. Youthfulness left my body that same evening, replaced by its next door neighbor. Nostalgia.

My grandfather departed from this world in October 2021. The figs he wanted to plant were rooted on his grave, and has since become a growing bush. When leaves grow on marble tombstones, they remind us of the time that stretches between the living and the dead. I felt a deep sense of relief when Baba Latif finally gave me his blessing to continue my historical studies. He wanted me to be a doctor because he thought I was trop douce (too gentle) to not go into the medical field. I never really understood the origin of the gentleness that he saw in me. He taught us all about how to be more like the qualities of his name. He taught us that we can carry kindness and love wherever we go, so long as it is in our hearts. His name was Abdelatif, and there is no name that would have suited him better.

I think our countless conversations on history and politics in a highly political summer might have changed his mind on the importance of my work, or maybe he recognized that history (and the humanities more broadly) required a sense of gentleness as well. In the summer of 2023, I visited his grave, and told him that I was going to Oxford. I did not tell him outloud, I just thought it. I thought it loudly enough in my head that an overwhelming sense of pride overcame me. Teary eyed, watching my mother’s silent tears as she poured water on the fig bush on Baba Latif’s grave, I felt his presence around me. The day Baba Latif died grounded me to Nabeul because that is where he lays, and is where I would want to be buried.

The world has become a darker place since he left.

I cannot send you this letter without mentioning what is going on now. With the ethnic cleansing happening in Gaza in the last few days, and the culmination of colonization of Palestine for decades, I have been imagining Baba Latif sitting opposite the television in disbelief and anger. As I write these words in a sheltered environment (Oxford), I find myself losing hope, and simultaneously slightly relieved by some of the displays of solidarity here. As the fight for ancestral land continues, as we stand against colonialism and apartheid, I am grieving the devastation and ruthless killing of Palestinians, present and past. We are all grieving in a world that sees Palestinians as subhuman. It feels like the world is constantly ending.

A homeland that one can return to, and return to it almost as if one never left, is not a given. In fact it is a privilege. And for that reason, we must to stand with our Palestinian brothers and sisters.

I pray for the living and for the dead. I hope that one day, the dead can rest peacefully, and those who survive them can visit their graves.

some parts of the dialogue of this piece is in Tunisian and translated into English. The Tunisian indicates a verbatim recollection of what Baba Latif said. When the text is only in English, it means it is an approximation of what we said to each other.

Things did in fact get worse. In the summer of 2021, Tunisia was experiencing the worse Covid-19 outbreak in Africa and among the Arab countries, with a healthcare system that was barely holding it together. This was the same summer that Kais Saied froze the parliament and since then, he has been gradually imprisoning his opposition. A footnote would not do justice to describe how bad things are now at the time of writing, but basic grocery goods like flour, sugar, milk and coffee are scarce, people are queuing for food, water is cut off at night in many cities, etc… Hindsight is a funny little thing.

she slayed again. crazy brazy

So touching, I like when you said you imagined him at anger and disbelief over the colonization of Gaza, it shows the depth of the connection and how you keep part of him alive.

I also admire the part where you told him at his grave of your departure to Oxford with pride, it’s so touching.